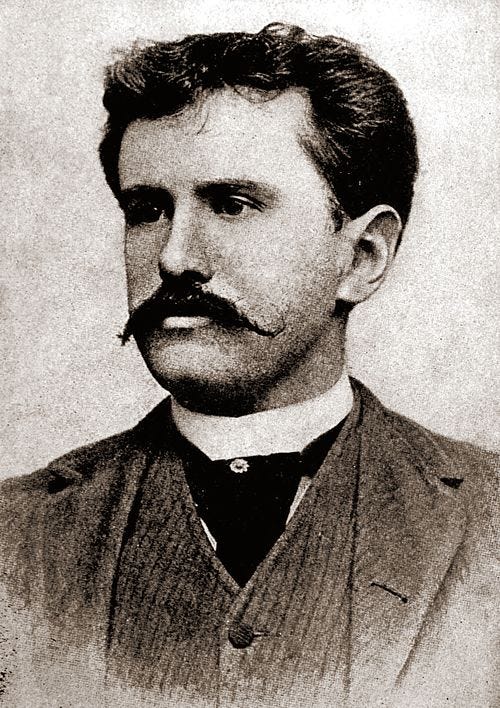

O. Henry: The Master of the Twist, Born in a Jail Cell

O. Henry: The Master of the Twist, Born in a Jail Cell

Picture this: it’s the turn of the 20th century in Austin, Texas. The air is warm, the town’s growing fast, but in a back office of the First National Bank, a young teller named William Sydney Porter is quietly digging a hole for himself he won’t escape for years.

Porter, whom the world would come to know by the pen name O. Henry, was accused of embezzling from the bank. Facing a federal trial, he fled to Honduras, where he dreamed up tales under the Central American sun and even planned a novel or two. But when his beloved wife, Athol, fell deathly ill, he did what any man of torn loyalty might do: he came home.

He surrendered. He was convicted. And in 1898, Porter stepped behind bars at the Ohio Penitentiary, sentenced to five years.

It was there, amid the iron bars and midnight lamplight, that he found the freedom he’d always been chasing. He started writing seriously. Short stories, those little windows into the everyday lives of clerks, beggars, swindlers, young couples, and dreamers. He mailed them out under his new alias: O. Henry. To editors in New York, the byline was mysterious, just another name on cheap newsprint. To Porter, it was a lifeline.

When he walked out of prison in 1901, three years served, for good behavior, he didn’t carry much. But he did have something invaluable: an audience. He headed for New York City, that bustling, hissing, magnificent metropolis, and made it his muse.

Over the next nine years, O. Henry published nearly 400 short stories, sometimes writing one a week, each with that signature ending: the twist that no one saw coming.

His world was the newsstand and the café, the cheap boarding house and the busy sidewalk. He wrote about clerks who fall in love, petty thieves who get outwitted, big-hearted dreamers who lose or win in ways they never expect.

His most famous piece, “The Gift of the Magi,” tells of Della and Jim, two poor lovers who sell their most prized possessions to buy each other gifts. The story ends with a gentle twist that has made readers smile (and ache) for more than a century.

Porter lived like he wrote; fast, witty, hungry for life. But his demons were never far behind. He drank heavily, his health failed him early, and by 1908, the man who could make an entire nation gasp with a last line was losing the words that once saved him.

On June 5, 1910, O. Henry died alone in a New York hospital room at age 47. Cirrhosis of the liver, diabetes complications, an enlarged heart. His life ended much too soon, but his stories did not.

To this day, readers still flock to his grave at Riverside Cemetery in Asheville, North Carolina. If you go, you might find small coins scattered on the stone, exactly $1.87, the same amount Della saved for Jim’s Christmas gift in The Gift of the Magi.

Locals say people have been leaving that amount on his grave for more than 30 years. The coins don’t stay long: they’re gathered up and donated to area libraries, a small, fitting tribute for a man who turned words into timeless magic.

There’s something deeply human about O. Henry’s stories: small people, big hearts, tiny moments that crack open to reveal a life’s worth of hope and heartbreak. His stories feel like the city itself; fast and unpredictable, comforting in the way they remind us we’re not alone in our foolishness or dreams.

Next time you gasp at a surprise ending, remember the man who was one of the most influential to do it first — writing in secret under a fake name, paying off debts with stories, turning a prison sentence into a passport to immortality.

That’s the real twist. And maybe the best one.