The Hustle That Holds Nigeria Together

The Hustle That Holds Nigeria Together

At 6:30 a.m., Zainab sweeps the tiled floor of her small gift shop in Lagos. She has her perfume boxes stacks and ties ribbons around gift baskets. No sooner had she arranged the hand creams in neat rows that her phone vibrated with new orders. This was even before she flips the “Open” sign. To her customers, she’s a reliable trader. To economists, she’s a data point inside Nigeria’s vast informal economy, a sector that employs four out of every five Nigerians and contributes about 65 percent of the country’s GDP.

Yet for all its weight, this economy lives without safety nets. Zainab works twelve hours a day, but she can’t get a business loan. Her rent is paid in cash. Her sole employee is unregistered. The government doesn’t count her in the official job statistics. Still, her daily hustle, multiplied by millions like hers, keeps Nigeria’s economy breathing.

The Invisible Majority

The Moniepoint Informal Economy Report 2025 calls it the “Nigeria’s growth engine.” Across the country, thousands of microbusiness owners were surveyed — barbers in Osogbo, food vendors in Bauchi, POS agents in Owerri, and boutique owners in Lagos. Their stories reveal a pattern of high energy, low protection.

The report estimates that informal enterprises generate nearly two-thirds of national output, yet most operate on margins thinner than a phone screen. About 79 percent of respondents said their costs have soared over the past year, even as 65 percent reported higher revenues. For many, sales growth hides a quiet erosion of profit. Inflation, which topped 33 percent in early 2025, has eaten through any gains.

It’s a world powered by self-belief rather than systems. In the words of the report: “Sales can rise, yet survival feels harder…Margins are still squeezed, and many operators remain in a perpetual state of financial fragility.”

The Faces Behind the Numbers

If you picture the informal economy as a swarm of street traders, you’d be partly right. But there’s a fuller picture behind the stalls and kiosks. Nearly four in ten informal business owners are between 25 and 34 years old. More than a third are women, often running their shops between school pickups or family care.

Take Aisha, a food vendor in Bauchi. She sells rice and beans by the roadside, earning about ₦18,000 on a good day. Her dream is to buy an industrial cooker to expand her menu, but no bank will lend to her. She has no collateral, no guarantor, and no formal ID beyond her voter’s card. Every few months, she pays “market development” fees to local authorities, yet none of it counts as credit history.

She laughs bitterly when asked, during one of our discussions, if she has a business plan. “My plan,” she says, “is to wake up tomorrow and still have customers.”

That story repeats across Nigeria. Women make up 35 percent of informal business owners, but nine out of ten earn below ₦250,000 a month. Their gender gap in access to finance is about nine percent, not massive on paper, but wide enough to shape destinies. The report also notes that women tend to reinvest more of their income into family welfare and education, meaning the informal sector’s gender imbalance carries a social cost beyond the balance sheet.

The Cost of Survival

A glance at Nigeria’s macroeconomy explains much of this pressure. The naira has plunged from ₦460 to over ₦1,400 to the dollar in two years. Petrol subsidies vanished. Transportation and raw materials have tripled in price. The result is a daily battle for equilibrium.

Small shop owners raise prices reluctantly, fearing they’ll lose customers. POS operators complain that cash scarcity kills business. Welders buy diesel at rates that consume half their profit. Meanwhile, every layer of government finds ways to tax them. One fruit seller I know in Port Harcourt told some researchers in 2023 that she pays “one ticket for the council, one for the union, one for the security boys.” None of those receipts will ever count toward formal recognition.

For many, digital tools are the lifeline. More than 70 percent of informal businesses now use mobile apps for transactions. But access to finance remains the mountain they can’t climb. Only 41 percent of respondents said they had ever received a loan for their business. Of those, most borrowed from cooperatives or friends, not banks.

The irony is painful: an economy that produces 80 percent of jobs is starved of affordable credit.

The Policy Paradox

Every government since independence has promised to “formalize” small businesses, yet most efforts vanish in bureaucracy. Experts interviewed in the Moniepoint report — including Dr. Chinyere Almona of the Lagos Chamber of Commerce and Industry — argue that Nigeria’s policies are rarely built on empathy for how informal workers actually live.

Inconsistent taxation, weak enforcement, and lack of coordination between agencies leave traders over-regulated and under-protected. The result is what can be better termed “regulatory schizophrenia.”

Still, there are bright spots. The government, in collaboration with SMEDAN and the Corporate Affairs Commission, has registered over 250,000 small businesses for free in the last year. Some state governments are introducing tiered tax reliefs for micro-enterprises. Digital platforms like Moniepoint and OmniRetail are also experimenting with data-driven credit scoring, using transaction history instead of collateral to determine eligibility.

But the gap between promise and practice remains wide. Foyinsolami Akinjayeju of EFInA puts it bluntly in the report: “The informal economy doesn’t need grand speeches; it needs practical tools that respect its realities.”

Moniepoint’s Bet on the Hustlers

Few understand those realities better than Moniepoint, a company that began by providing POS machines to small merchants and now processes over $250 billion in annual digital payments. The company’s strategy is simple: bank the unbanked by embedding financial services directly into their daily lives.

Through its platform, a market trader can register a business, receive payments, access credit, and pay taxes — all within one ecosystem. The firm claims that its tools have helped quadruple the number of businesses that formalized operations in the past year.

It’s a bold experiment in “inclusive infrastructure.” Instead of forcing microbusinesses to climb the ladder of bureaucracy, the platform lowers the ladder to their level. The model works because it mirrors how Nigerians already operate, which is through trust and speed.

The Spirit of Enterprise

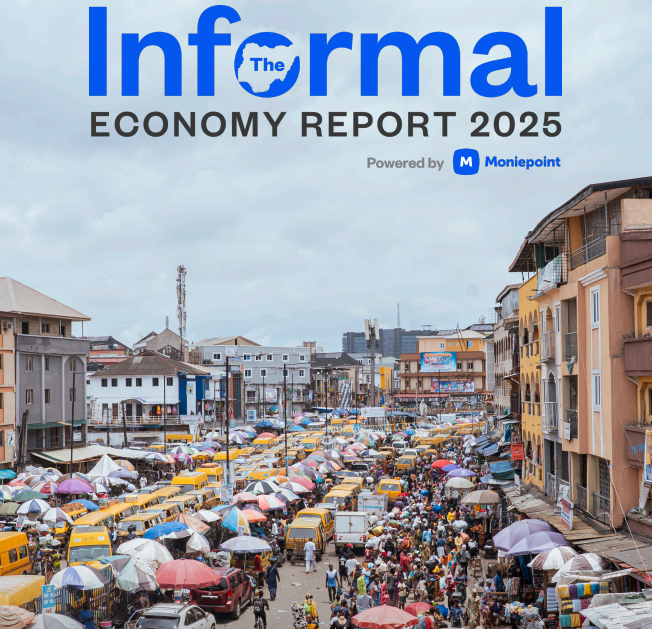

To understand the informal economy’s resilience, you need only stand at a Lagos junction at dusk. You’ll see young men chasing after vehicles with bottled water, women balancing trays of boiled groundnuts, teenagers selling phone chargers through open windows. None of them are in official employment data, yet they keep the city moving.

A professor once described Nigeria’s informal sector as “a parallel economy born of necessity.” It’s also a portrait of creativity. Street vendors adopt mobile payments faster than many corporate firms. Tailors on Instagram market with more flair than some advertising agencies. Amid hardship, people invent ways to survive, and sometimes to thrive.

Still, the human cost is real. Many operators work without health insurance, retirement savings, or legal protection. When illness or theft strikes, businesses collapse overnight. The Moniepoint report estimates that up to 40 percent of small enterprises fail within three years. Most never reopen.

Lessons from the Numbers

The data paints a paradox. The informal sector sustains Nigeria, but the system treats it as temporary; something to be tolerated, not empowered. Policymakers often speak of “migrating” these businesses into the formal economy, as though they were refugees seeking asylum. Yet formality without support can be lethal.

If Nigeria mainstreamed cash-flow lending and goal-based savings, as the report suggests, business closures after shocks could fall sharply. If regulators offered consistent tax incentives instead of random levies, more traders would register voluntarily. If women entrepreneurs had equal access to microloans, millions of families would escape subsistence living.

The solutions aren’t mysteries. They’re matters of will.

What the Future Holds

The informal economy is growing faster than the formal one. That should worry policymakers but also inspire innovation. Across Africa, countries like Kenya and Rwanda are showing what’s possible: digital IDs and cooperative insurance schemes that treat micro-entrepreneurs as partners, not afterthoughts.

Nigeria has the scale to lead that transformation. The entrepreneurs are ready. The question is whether the state will catch up with its own people.

The Light That Refuses to Go Out

As night settles in Lagos, Zainab locks her shop and joins a short queue at a nearby POS stand. She transfers money to her mother in Ilorin and checks her sales for the day. She earned a little less than she hoped, but enough to restock. Her phone buzzes again. It’s a new order, a new day waiting.

Her business may be small, but it tells a larger truth of the informal economy is not being Nigeria’s shadow. It is the light that refuses to go out, even when the system around it flickers.

And until that light is seen for what it truly is — not a problem to fix but a foundation to build on — Nigeria’s future will keep resting on the shoulders of its hustlers, who keep faith where policy falters.

You can download the report here.