Obituary - Giorgio Armani, The Reluctant Designer

Obituary - Giorgio Armani, The Reluctant Designer

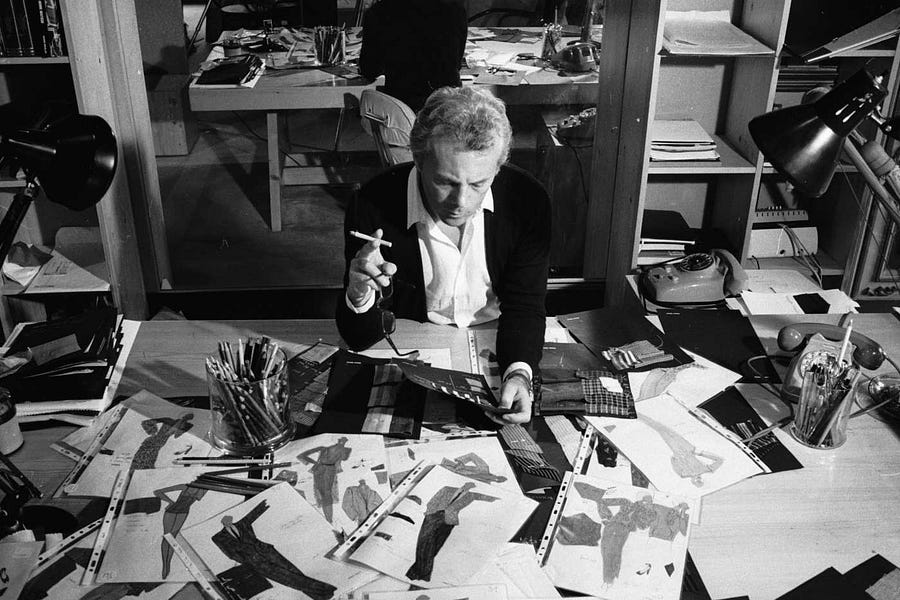

Today, the world lost Giorgio Armani. He was 91, and right until his final months he was still sketching designs and arguing about light fixtures before his shows. A man who started his professional life studying medicine ended it as the architect of the largest privately owned luxury brand on earth. In death, his name carries the weight of both a style and a system. Even as a kid in lowly Ilorin, I knew that Armani is shorthand for elegance. But in adulthood, in the abundance of books, I came to understand that it is also a business model.

Armani’s story began in Piacenza, south of Milan, in 1934. His childhood carried the marks of war. When he was not yet ten, a mine explosion left him badly injured. Doctors swathed his eyes in bandages for weeks, uncertain if he would ever see again. He remembered the smell of linden trees outside the hospital more vividly than the pain. That memory stayed with him.

He went on to study medicine at the University of Milan. A brief stint in the army followed. His medical training placed him in an infirmary, but he never felt it was his calling. Fashion arrived by accident. A temporary job at La Rinascente department store as a window dresser opened doors. He was promoted to buying supervisor, sourcing goods from India, and the United States. Soon after, he was designing for Nino Cerruti, the Italian businessman and stylist.

By 1975, with Sergio Galeotti, his business and romantic partner, he founded Giorgio Armani. They sold their Volkswagen Beetle to raise the funds. What he launched that year became one of Italy’s greatest cultural exports.

At a time when Savile Row still ruled the male silhouette, Armani took the scaffolding out of the suit. He softened the internal structure, removed heavy padding, and let fabric fall closer to the body. His men looked less like bankers, more like themselves. His women wore versions of those suits too, sharp and professional, but without the stiffness that had defined female workwear until then.

The turning point came in 1980. Richard Gere, playing a high-end escort in American Gigolo, wore Armani. His louche sensuality, displayed in scenes where he carefully lays out Armani jackets across a bed, helped introduce the brand to mainstream America. Suddenly the world wanted that mix of confidence and ease. In boardrooms and corner offices, Armani became uniform.

As fashion historian Harold Koda once noted, Armani’s achievement was not only about design but about what his clothes meant socially. Like Chanel with the little black dress, Armani gave people a new code. His softened suits provided armor without rigidity. For women entering the workplace in the 1980s, those jackets became a kind of passport. They projected competence without hiding femininity.

Armani understood the camera. Cinema was his first love, and in interviews he often said he might have been a director had life gone differently. He opened an office in Los Angeles in 1983. No other European designer had done that. He was there to dress actors, to make Hollywood his runway.

It worked. Jodie Foster, clad in Armani, won an Oscar in 1992 and landed on best-dressed lists. Michelle Pfeiffer became a muse. Julia Roberts, Cate Blanchett, Lady Gaga, and Zendaya wore him on red carpets. He created costumes for films from The Untouchables to The Wolf of Wall Street. His tuxedos became the standard for Russell Crowe and George Clooney. Armani turned celebrity dressing into a business practice. Today every fashion house does it. He was first.

By the 1990s, Armani was no longer only a fashion designer. His group expanded into Emporio Armani, Armani Exchange, fragrance, cosmetics, homeware, hotels, restaurants, even sports sponsorships. He dressed the Italian Olympic team and owned Olimpia Milano basketball. His partnership with Ferrari Formula One brought the brand to racetracks. The Armani logo could appear in a perfume ad, on a basketball jersey, or on a five-star hotel in Dubai.

He never sold out. French conglomerates acquired most rivals. Armani resisted. He created the Giorgio Armani Foundation to protect his company from takeover, ensuring it would remain private even after his death. In 2023 his brand posted revenues over €2.5 billion. He himself amassed a fortune estimated at €12 billion, yet he lived by strict habits, often eating dinner alone with his cats, watching television.

Not everything about Armani’s career was polished. In 2015, he caused controversy by suggesting gay men “do not need to dress homosexual.” His company reached a tax settlement in 2014 over offshore subsidiaries, though without admission of wrongdoing. Critics accused him of repetition, of playing safe while others innovated with louder palettes.

He also knew grief. Galeotti, his partner, died of complications related to AIDS in 1985. Armani shouldered the company alone from then on. Friends said he worked like a man holding his breath. He expected his staff to share his discipline. At fittings and shows, he would correct details down to the half-centimeter. An aide once recalled him saying a tie was too long by precisely 1.5 cm, enough to throw off the outfit’s balance. His perfectionism could intimidate. It also defined his empire.

Italy treated him as a national treasure. He received the Italian Order of Merit for Labour. France awarded him the Legion of Honour. Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni called him “a symbol of the best of Italy.”

Colleagues echoed that tone. Donatella Versace said, “The world lost a giant today.” Vogue’s Laura Ingham reminded readers that even people uninterested in fashion knew Armani. Russell Crowe called him a man who “made a mark acknowledged around the globe.”

The Financial Times profiled him in one of his last interviews, noting that he gave women uniforms as radical as Chanel’s and reshaped menswear permanently. Alexander Fury, the journalist, observed that Armani’s relaxed tailoring “has affected how just about every suit in the world is made.”

The final years

Armani continued working into his tenth decade. His 2025 shows in Paris and Milan included references to global politics. He spoke of harmony, saying it was “what we all need.” Concerns about his health surfaced when he missed Milan Fashion Week in June 2025. In July, he directed a couture show remotely from his Milan home. His final bow in January, alongside model Agnes Zogla, was emotional. Audiences stood for minutes, knowing they were watching a closing chapter.

When his death was announced, his company called him “indefatigable to the end.” He worked until his final days, designing, reviewing, planning. His burial will be private, but a chamber at the Armani headquarters will allow mourners to pay respects.

Armani’s empire is vast, but his succession remains uncertain. Nieces Roberta and Silvana work in the company. Nephew Andrea Camerana sits on the board. Pantaleo Dell’Orco, who worked with him for 46 years, runs menswear. The Giorgio Armani Foundation will hold a stake to keep the company intact. But the weight of his personal influence was enormous. Insiders admit the void may never be filled.

His legacy is clear though. He gave the world a new way to see the suit. He showed Hollywood how fashion and film could dance together. He kept his company private when others sold, ensuring independence as part of his identity. He insisted elegance could be quiet, and that confidence needed no noise.

Armani once said he chose work as his way of life. Until the end, he kept that choice. His legacy is stitched not only in fabric but in culture. For millions of people, from actors on the red carpet to professionals walking into offices, Armani was the look of authority, of grace.

The world will keep wearing his vision, even if he is no longer here to perfect the ties.