Book Review - ”Everything Is Tuberculosis” by John Green

Book Review - ”Everything Is Tuberculosis” by John Green

Book Review — “Everything Is Tuberculosis” by John Green

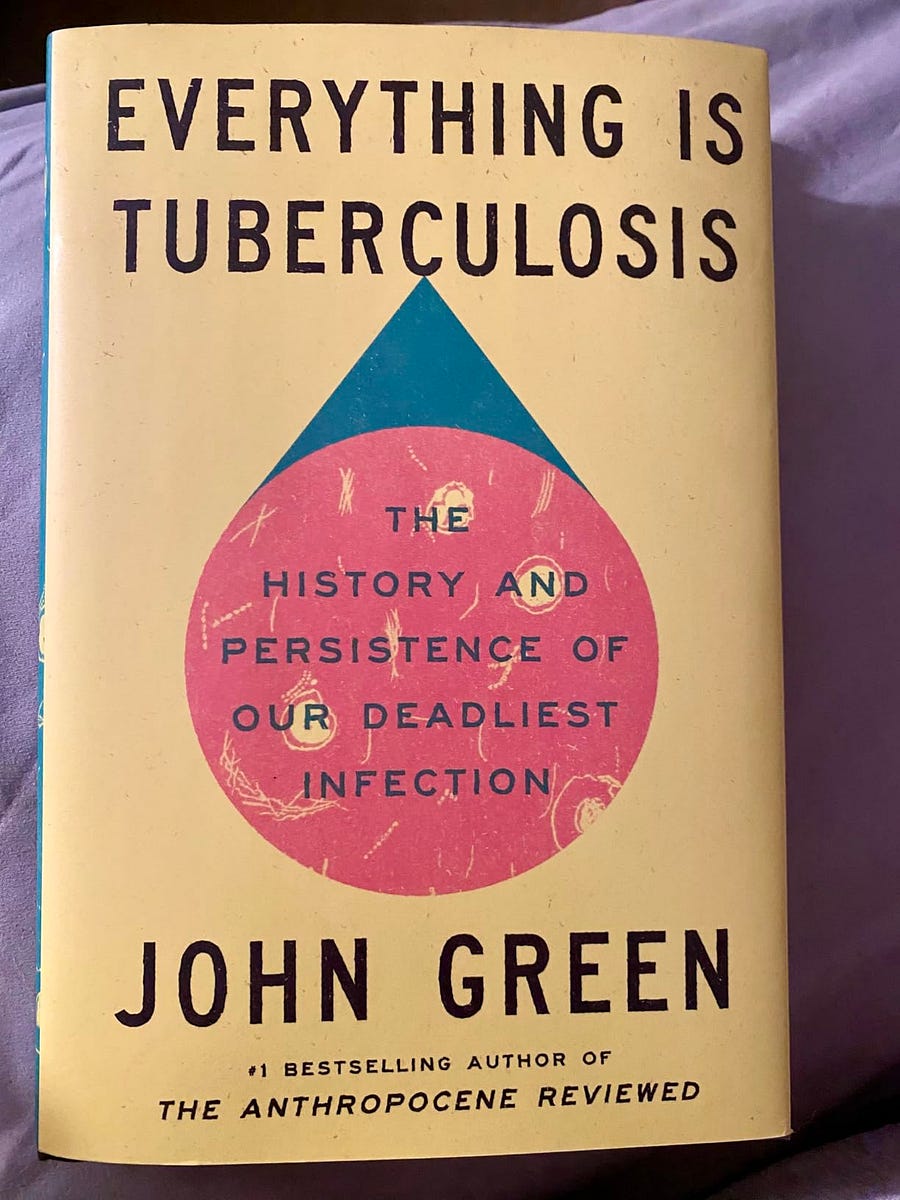

When John Green announced that his next nonfiction work would not be about literature or teenage angst but tuberculosis, I was skeptical. We know Green; his novel The Fault in Our Stars is one of the best-selling books of all time. Now, a 170-page book on Tuberculosis? When did this splendid writer become an Infectious Disease Specialist? Yet Everything Is Tuberculosis: The History and Persistence of Our Deadliest Infection (March 2025) is anything but a dry medical history. So you don’t get disappointed like a fellow who read the book on my account and criticized it for not being as explosive as Parasite Rex by Carl Zimmer, know that this book is part memoir, part indictment of global negligence. More importantly, it is part elegy for the millions who continue to die from a disease we have technically known how to cure for seventy years.

The surprise for many is that Green does not begin with statistics or research papers but with Henry Reider in Sierra Leone. Meeting Henry in 2019 altered the course of his life. Henry endured TB not as an abstract illness but as a brutal, intimate tragedy. His family bore its scars, and his recovery was hard-won. It was Henry’s suffering and resilience that convinced Green to use his unlikely megaphone, earned through bestselling novels, to amplify the silenced voices of patients and caregivers. Green confesses that without Henry, this book would not exist.

This grounding in human pain makes the book more than a survey of facts like many books on infectious diseases.

#DidYouKnow Tuberculosis was colloquially called consumption because of the suffering it gives and the physical wasting of the body it wrought.

Tuberculosis is not ancient history. It is our present. In 2023, after COVID’s brief reign, TB reclaimed its title as the world’s deadliest infection, killing 1.25 million people in a single year. Frank Ryan’s estimate that TB has killed one in seven humans who ever lived is repeated with appropriate weight. The disease is both old and insidious, mentioned in ancient Chinese and Greek medical texts under names that translated to “lung exhaustion,” “wasting away,” or “decay.” Hippocrates himself warned his students not to treat phthisis (another name given to TB) because it was a losing battle.

Green is at his best when drawing these long arcs of history. He ties Hippocrates’s despair to the weight loss and wasting still seen in patients today. He explains why TB was known as “consumption”; it consumed the body from the inside out. He layers in cultural images, from Daoist priests calling it “corpse disease” to Charles Dickens naming it the ailment “wealth never warded off.” The roll call of victims is staggering: Kafka, Keats, three Brontë sisters, Simón Bolívar, Eleanor Roosevelt, and countless others. Tuberculosis has always been an egalitarian killer.

The book is filled with surprising digressions. TB gave us the cowboy hat. TB helped make New Mexico a destination, marketed as a place where clean desert air might heal frail lungs. TB even played a minor role in the chain of events that sparked World War I. These odd connections help lighten the otherwise heavy narrative and remind readers that diseases, like people, shape cultures in unexpected ways.

Even stranger is the disease’s unpredictability. Between 20 and 25 percent of people recover from active TB without treatment, for reasons science still cannot explain. About 90 percent of infected individuals never fall sick at all, while the unlucky 10 percent progress to active illness and risk spreading it to ten or fifteen others each year. This mix of dormancy and disaster has long made TB one of medicine’s trickiest foes.

Yet Green does not only chronicle. He rages. He criticizes the global medical bodies for their cautious bureaucracy. He lashes western countries for failing to support poorer countries where TB thrives. His critique sometimes overreaches. By placing all the blame on colonial legacies and Western neglect, he brushes aside the role of the governments of developing countries that underfund their own healthcare systems. As a reader who knows the Nigerian and by extension the African context, I found this one-sided. Green sees global donors as indispensable, and he is right about their importance. But local responsibility cannot be erased. Tuberculosis persists not only because of global indifference but also because of weak national commitments.

This imbalance is one of the book’s flaws. Green is so emotionally invested in telling the story of Henry and others like him that his political judgments tilt too easily toward outrage rather than balance. Yet even in this, the book succeeds in provoking reflection. It forces us to confront the uncomfortable fact that TB remains curable and yet is allowed to kill over a million people each year.

The most moving passages come not from medical history but from Green’s candid reflection. He admits he never thought much about TB until Henry entered his life. He confesses to guilt: What if he had used his fame earlier, when millions of his fans hung on his every word? What if his megaphone had carried not novels but urgent calls for health justice?

This makes Everything Is Tuberculosis more than a history book. It is Green’s personal reckoning with privilege and responsibility. He writes as someone haunted, not detached. The book is laced with mourning, but also with a search for meaning in the resilience of patients and in the stubborn fight of caregivers.

The book is slim at about 170 pages, but its brevity is an asset. It distills millennia of myths and science into a clear narrative, accessible to general readers. More importantly, it makes TB personal again. In the West, where antibiotics and vaccines lull into complacency, TB is invisible. Green tears down that invisibility.

He reminds us that TB kills in the prime of life, that it has been called “the robber of youth,” and that it once defined entire centuries. By telling Henry’s story alongside that of emperors and poets, he bridges the gap between global health statistics and human heartbreak.

For readers new to the subject, Everything Is Tuberculosis is a revelation. For those familiar with public health, it is a reminder of how personal stories give life to global issues. And for John Green, it is proof that even novelists can wield their fame in service of forgotten battles.

Henry Reider’s suffering set this book in motion. John Green’s words ensure it will not be forgotten.